Acid and pH

The most in depth explaination of acid and pH levels in each portion of our digestive system and how each plays in intricate part in treating your baby's acid reflux.

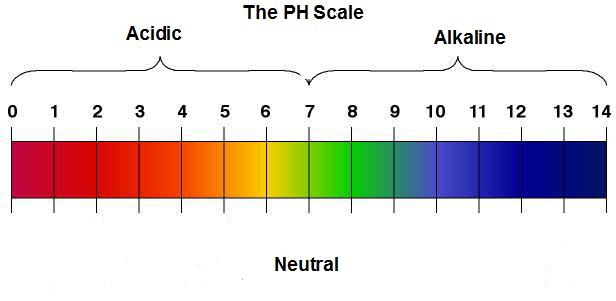

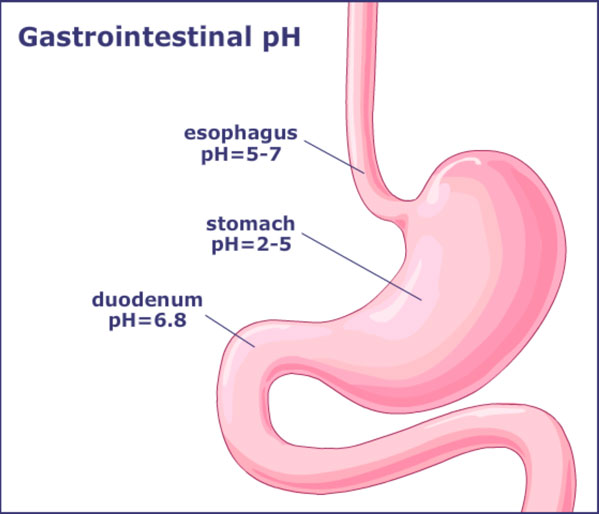

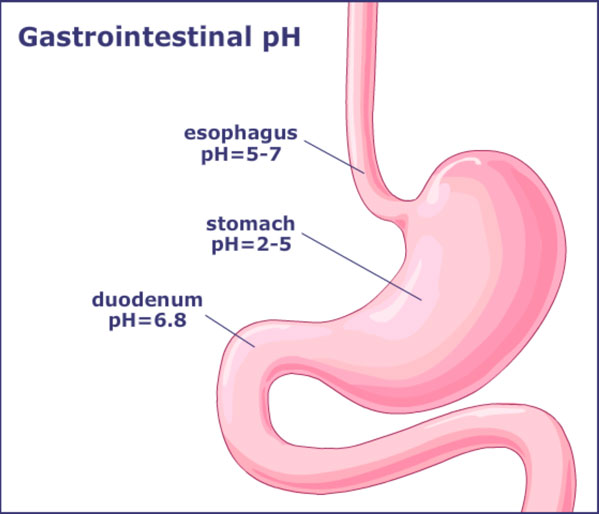

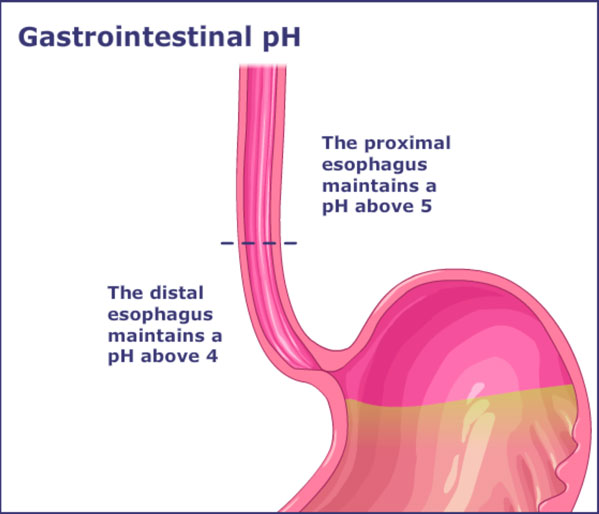

Gastrointestinal acid and pH ranges from zero (acidic or red), seven (neutral or green), to fourteen (alkaline blue) and pH levels vary throughout the gastrointestinal tract which is made of the esophagus (upper and lower), the stomach and the small Intestine.

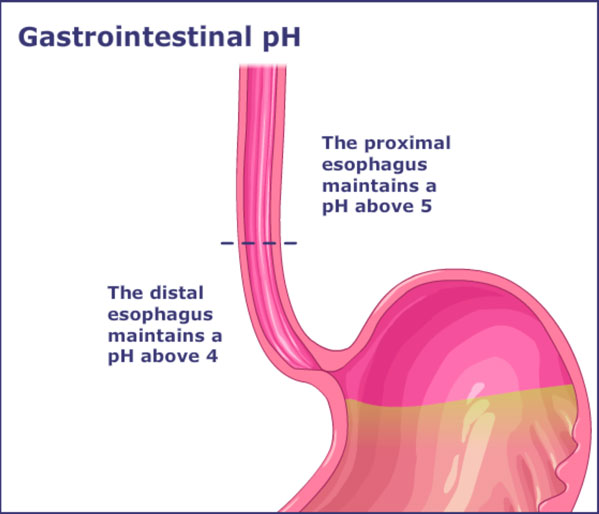

The Esophagus: Should have a pH level ranging from five to seven. It is divided anatomically into proximal or upper esophagus and distal or lower esophagus.

Proximal Esophagus / Upper Esophagus:

The pH of the upper esophagus should be a pH level of higher than five and is often

five to seven. The amount of time that the esophageal pH measures less

than five is a standard for diagnosing reflux problems. (A pH greater than five must

be maintained in the upper

esophagus to heal damaged tissue).

Distal Esophagus / Lower Esophagus: The pH of the lower or distal

esophagus should be more than four and is often five to seven. When you

are trying to diagnose the potential of infant acid reflux it's

important to measure the level of pH within a twenty-four hour period.

If the esophageal pH measures less than four it is a common pH level for

diagnosing reflux problems in the lower esophagus. (A pH level greater than four must be maintained in the lower esophagus to heal damaged tissue).

Stomach: The pH of the stomach should range between 1-5 but the pH of the stomach varies throughout the day, depending on the amount of food that is contained in the stomach. Overall, it is rather acidic because of the parietal cells pumping out stomach acid necessary to break down food as it is ingested, which has a pH as low as 0.8. On empty stomach however, the pH can be as low as one rising to close to five after a full meal.

Gastric pH drops while sleeping without food to help neutralize the acid and is called "Nocturnal Acidity" also known as "Acid Dump". Lying flat while sleeping is the perfect opportunity for the acid to cause damage to the esophagus and airways and cause symptoms such as night time awaking, coughing fits, and choking.

Small Intestine: The acid and pH levels of the small intestine should maintain 6.8. The duodenum, the first ten to twelve inches of the small intestine, is significantly less acidic than the stomach. This difference is relevant to the way that enteric coated drugs are made to work. The coating dissolves at the more neutral pH, releasing the drug and allowing it to be absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal wall.

How The Body Naturally Minimizes Gastric Acid

The body's natural line of defense against Hydrocholoric Acid (stomach acid) is shown below in the interactive graphics. These represent each section of the gastrointestinal tracts and the process that occurs.

In each of the three sections of the gastrointestinal tract (Esophagus, Stomach, Small Intestine) there lays their own mechanisms for protecting against the dangerously low pH of stomach acid by either keeping acid away from sensitive tissue or neutralizing acid that already exists.

The Esophagus

Peristalsis: clears the esophagus by pushing stomach contents back into the stomach; gravity also aids this process.

Saliva naturally contains bicarbonate, a chemical that helps to neutralize acid in the digestive tract.

Layers of cells called stratified squamous epithelium line the esophagus and keep acid from seeping in deep enough to do serious damage.

Mucous glands in the wall of the esophagus secrete a protective lubricant.

The Stomach

Mucus-secreting cells coat the entire surface of the stomach with a thick layer of mucus that has buffering, lubricating and antibacterial properties.

A high turnover rate to replace damaged cells allows surface mucous cells to renew themselves every 3-5 days.

Tight junctions (arrow) between the epithelial cells act as a seal to prevent acid from seeping between the cells and into the stomach lining.

The parietal cell’s membrane is highly impermeable to acid, protecting the cell from acid degradation.

The Small Intestine

Pancreatic juices containing bicarbonate are secreted into the small intestine. This neutralizes much of the acid leaving the stomach.

Glands in the wall of the duodenum (first segment of the small intestine) also secrete bicarbonate.

Step A: Gastric Minimization of Acid and pH in the Esophagus. Saliva naturally contains bicarbonate, a chemical that helps to neutralize acid in the digestive tract. When food is ingested the saliva glands go into action to immediately neutralize any acid in the food that is being eaten.

Mucous Glands in the wall of the esophagus secrete a protective lubricant in addition to the saliva. Peristalsis clears the esophagus by pushing any stomach acid contents back into the stomach. Gravity also aids in this process. Meaning, when an adult is standing up right, the adult has more of a gravity effect that aids in keeping food moving in the direction intended.Stratified Squamous Epithelium Cells are layers of cells that line the esophagus and keep acid from seeping in deeply enough to do damage.

Step B: Gastric Minimization of Acid and pH in the Stomach Mucus-secreting cells coat the entire surface of the stomach with a thick layer of mucus that has buffering, lubricating and antibacterial properties.

Tight junctions (see arrow) between the epithelial cells act as a seal to prevent acid from seeping between the cells and into the stomach lining.

A high turnover rate to replace damaged cells allows surface mucous cells to renew themselves every three to five days.The parietal cell's membrane (the cell that produces acid)is highly impermeable to acid and it protects the cell from acid degradation.

Step C: Gastric Minimization of Acid and pH in the Small Intestine: Pancreatic juices containing bicarbonate are secreted into the small intestine which neutralizes much of the acid leaving the stomach.

Glands in the wall of the duodenum (the first segment of the small intestine) also secrete bicarbonate.

Contents of this page originate from the Maci-Kids website and

from Jeffrey Phillips Pharm D's research in treating infants with acid

reflux. This concludes the information on acid and pH. If you have any questions please connect with us so we can help!

For those users on Firefox you can view the interactive flash images below.

FIGURE 1

pH varies throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

( Click on the image above for more details. )

Esophagus

Peristalsis: clears the esophagus by pushing stomach contents back into the stomach; gravity also aids this process.

Layers of cells called stratified squamous epithelium line the esophagus and keep acid from seeping in deep enough to do serious damage.

Saliva naturally contains bicarbonate, a chemical that helps to neutralize acid in the digestive tract.

Mucous glands in the wall of the esophagus secrete a protective lubricant.

Stomach

Mucus-secreting cells coat the entire surface of the stomach with a thick layer of mucus that has buffering, lubricating and antibacterial properties.

Tight junctions (arrow) between the epithelial cells act as a seal to prevent acid from seeping between the cells and into the stomach lining.

A high turnover rate to replace damaged cells allows surface mucous cells to renew themselves every 3-5 days.

The parietal cell’s membrane is highly impermeable to acid, protecting the cell from acid degradation.

Small Intestine

Pancreatic juices containing bicarbonate are secreted into the small intestine. This neutralizes much of the acid leaving the stomach.

Glands in the wall of the duodenum (first segment of the small intestine) also secrete bicarbonate.